Privilege at Play Book Review

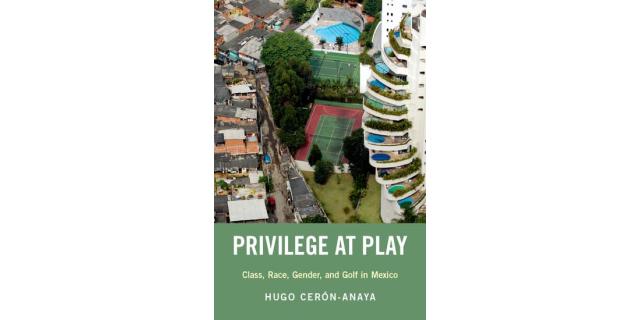

Hugo Ceron-Anaya’s book, Privilege at Play: Class, Gender, and Golf in Mexico (2019), probably wasn’t written to be read by me. The book’s main audience is academic sociologists, not half-witted hacks on a deadline. Nevertheless, its title and the publisher’s back copy perked my interest and one very hurried email to Oxford University Press (asking for a review copy) and several weeks of procrastination later, here we are. My review is finished and published. My judgement? I found Privilege at Play to be thought-provoking, entertaining and informative, though wasn’t always convinced by its analysis.

As a layperson or, at any rate, not a trained sociologist, I have probably missed many of the books’ finest (in both senses of the word) points. But I felt like I got a good hold on Ceron-Anaya’s main arguments and found the work relatively easy to follow. Privilege at Play presents an informative and stereotype-busting history of the golf in Mexico and an analysis of how golf and golf clubs contribute to building class, racial and gender identities and undergirding various social hierarchies. This may sound like heady stuff, but don’t be put off. Unlike some academic books, Privilege at Play is well-written, even journalistic in its verve and clarity, and, though, as I’ve noted, its main audience is undoubtedly fellow academics, it is refreshingly accessible to the general reader. It has a clear structure and its arguments are well laid-out. Judging from the reviews on the publisher’s back copy, the mind’s best placed to assess these have been convinced by them. It is to Ceron-Anaya’s credit that this half-baked reviewer could glean enough to be (with a few exceptions) convinced by them too.

Golf, according to Ceron-Anaya, is more than just a game: it is a marker of status, a way of building bonds between powerful groups, and, concomitantly, of excluding and oppressing weaker groups, staking out the class, race and gender boundaries within and around which we all operate. He makes a strong argument. One of the key strategies deployed is analysing the way in which the sport is described and the language and images which surround it. I found this analysis fascinating, enlightening and frequently enjoyable to read. Ceron-Anaya has that rare ability to pierce below the surface of a phrase and to plumb the hidden ways in which language operates. Thus, he notes that Donald Trump’s defence of golf’s elitism – “golf is never going to be basketball” – has a racial edge, basketball being very “strongly associated with African American athletes”. At several points in the book, he digs for power structures in the etymology of the Mexican language and very frequently strikes gold. Did you know, for example, that the popular Mexican insult ‘naco’ can mean not only “someone who is ignorant, clumsy, and lacks education” and “someone who lacks taste or class”, but also an “Indian or Indigenous of Mexico”. Despite, the common assumption that race distinctions do not exist in Mexico, Ceron-Anaya’s vaunts into the undercurrents of everyday speech shows that they do. They’re just very subtle, so deeply embedded that they’re invisible to the fast-moving eye.

Sometimes though, I thought that Ceron-Anaya overstretched his analysis. The fact, for instance, that popular images of golfers and their caddies foregrounded the former isn’t, to my mind, as sinister as the academic claims. Similarly, I wasn’t quite sure what to make of some of Ceron-Anaya’s analysis of some of his interviews, conversations which he has with upper-class and middle-class golfers, and which form a key part of the evidence in the book. At one point, he takes issue with golfers describing a fellow player as cheap and aggressive, implying that their judgements are not to be trusted. However, it is unclear why this should be the case. If, as the interviewee says, the fellow player complained about the size of a tip a group are leaving, then I think it’s fair to say that they’re stingy with money, and if a person spends the best part of the day whining about losing a tournament, I think it’s also fair to say that they are too emotional. For Ceron-Anaya, the golfers’ descriptions of the unpopular player represented an apparently calculated “association of lower-class origins with aggressiveness, anger, and lack of emotional self-control”. But is it not possible that class had nothing to do with it? Why could the golfer have not just been badly behaved?

Two other things about the book bugged me. First, the slippage which Ceron-Anaya identifies between class and race. Again, by and large, I strongly agree with him: lots of times, in his examples, the language of class does seem to work as a veiled way of talking about race. But I have some reservations about his claim that money “whitens” and, especially, his choice of this term. ‘Whiteness’ seems to be being used to describe something that goes further than white skin, which is precisely where I think the use of the word falls down. One could argue that Ceron-Anaya risks naturalising the association between white skin and socio-economic standing, which, while perhaps true in Mexico, is not unilaterally true across the rest of the world. This has real world consequences. If, as Ceron-Anaya and many others believe, language is integral to shaping our world, then doesn’t linguistically smudging together skin colour and affluence risk simultaneously smoothing over the existence of the white working class, where white skin is meshed not with riches but with poverty? On a linguistic level, it engineers them out of existence.

Secondly, while I agreed with a lot of the analysis, I would have liked to have seen more solutions. Though I know that academia typically resists this, I would have liked for Ceron-Anaya to have nailed his colours a bit more firmly to the sociological mast. Throughout the book I detected (or, perhaps, imposed) a distaste for the average Mexican golfer that, as I’ve noted, seemed to leak into a sometimes unreasonable skepticism about their characters and responses to his questions. At the end of the book Ceron-Anaya cites research showing the deleterious effects of disparities in wealth. This makes sense. But what would Ceron-Anaya have us do about it? Would he ban members only golf clubs? Raise taxes? What’s the solution? I sensed a strong ideological edge in the book that never quite wriggled through to the fore. Sometimes, this seemed to prevent neutral analysis.

On the whole, however, I found Privilege at Play an enjoyable and informative read. Its arguments largely convinced me and I learned much about golf and Mexico. Excepting my stated quibbles, I closed this book a satisfied and better educated general reader.

For more information, click here.